Indigenous and Ancient Rooted Permaculture Techniques

Indigenous practices have influenced permaculture fundamental ethics and practices. This indigenous knowledge, often referred to as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), formed a significant foundation for modern permaculture design systems.

Specific practices and principles

-

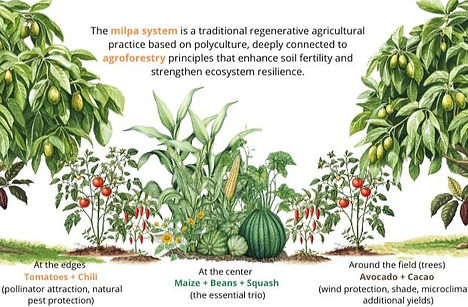

Companion planting: Practices like the Three Sisters system, where corn, beans, and squash are planted together, are a core part of permaculture. The corn provides a trellis for the beans, the beans add nitrogen to the soil, and the squash shades the ground to retain moisture and suppress weeds.

-

Soil health: Indigenous peoples used methods like planting nitrogen-fixing legumes to improve soil fertility, a practice that reduces the need for fertilizers in modern permaculture.

-

Biodiversity:

-

Seed saving: Indigenous communities carefully saved seeds for millennia, preserving a vast diversity of crops that are adapted to different conditions and are crucial for agricultural resilience.

-

Companion planting: Beyond the Three Sisters, the general practice of pairing mutually beneficial plants is a key permaculture principle that reduces pests and increases crop health.

-

-

Holistic Management:

-

Working with nature: Indigenous methods often treat land as a whole system, focusing on working with natural patterns rather than against them. This contrasts with imposing designs onto the land.

-

Prescribed burning: Some groups, like the Chumash and Yurok, used carefully managed, small-scale prescribed burns to clear underbrush, regenerate land, and prevent larger wildfires.

-

-

Community and reciprocity: Indigenous systems often emphasize communal effort in planting and sharing resources, along with a reciprocal relationship with the land, which are principles modern permaculture seeks to embody.

-

Crop rotation: This centuries-old practice is used by indigenous peoples to enhance soil fertility and prevent pests and diseases, and is a staple of permaculture.

Milpa Gardening

Stages

1. Turning forest into field

- This is typically done by using slash and burn, then annual crops are planted to keep the soil covered.

- 4-5 years

2. Field to orchard

- Fruit trees and fast-growing perennials are planted. This allows for slow growing perennials to reach maturity.

- 4-12 years

3. Orchard into forest garden

- Perennials have reached maturity and are producing. Another milpa will be started.

- 12 -20 years

4. Forest regeneration

- The forest ends up turning back into a hardwood forest. The forest might be left alone or harvested again.

- 20+ years

Vision

Industrial plowed field on the left shows soil damage. But the Maya used agricultural practices centered on the milpa cycle on the right, which leads to healthier soil, water conversation, and many more benefits.

Fire Management

Environmental Benefits

-

Reduces wildfire risks

-

Improves soil health

-

Promotes plant and animal life

-

Restores habitats

-

Allows for biodiversity

-

"Cultural burning” refers to the Indigenous practice of the intentional lighting of smaller, controlled fires to provide a desired cultural service, such as promoting the health of vegetation and animals that provide food, clothing, ceremonial items and more.

-

Tribal philosophy of fire as medicine.

Click the image to learn more about Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs)

Coppice

-

Coppicing is an ancient woodland management technique that was once used to ensure a regular supply of timber and firewood.

-

Dates to the Stone Age.

-

-

Coppicing also mimics a natural process where large mature trees fall due to old age or strong winds, allowing light to reach the woodland floor and giving other plant species the opportunity to thrive. This can start a chain of events that hugely increases the range of plants and wildlife in a woodland area.